For any first-year student, university classes can seem scary. Add in a learning disability and it’s easy to be overwhelmed. Just ask Lauren Goegan.

Now a post-doctoral researcher in the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Education, she vividly recalls one of the first lectures she attended as a new undergraduate with dyslexia.

The class was delivered through images – no words, no notes – the instructor was talking a mile a minute and she wrote frantically, trying to keep up. For someone with difficulties processing language, it was discouraging.

“I remember coming out of class and thinking, ‘I don’t know what I wrote,’” said Goegan, who recently published a study exploring the connection between student characteristics, academic and social integration, and various outcomes such as satisfaction levels for students with learning disabilities (LD).

Affecting everything from retaining class lessons to finding the way around campus, learning disabilities ramp up the already stressful experience of starting a post-secondary education.

“Navigating a new environment adds an extra layer of stress, anxiety, even fear because a lot of students with LD don’t want to disclose that, so it can be more difficult to make friends in post-secondary than in the school system where the kids knew you.”

“Navigating a new environment adds an extra layer of stress, anxiety, even fear because a lot of students with LD don’t want to disclose that, so it can be more difficult to make friends in post-secondary than in the school system where the kids knew you.”

Her research, published in Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, showed that while students with LD come into post-secondary education with the same hopes as any other student – making friends, learning new things and earning their degrees – social connection is especially critical to their success on campus.

“That sense of belonging is really important to outcomes like satisfaction or learning important skills,” Goegan said, noting that research shows students with LD have a post-secondary completion rate of 41 per cent compared with 52 per cent for their peers.

“If you feel like you belong at university, you’ll feel more satisfied with the experience. So social integration is an important way to support them.”

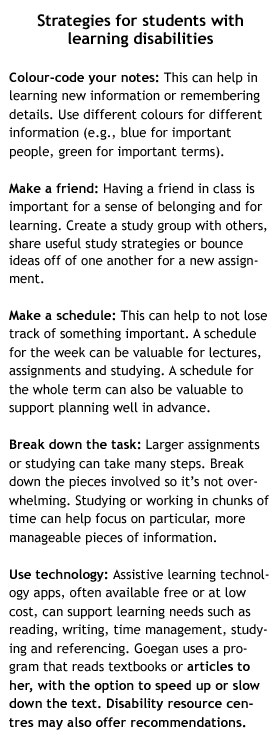

There are several ways to support students with LD, she suggested.

Post-secondary and other school systems can focus awareness on the issue through class and club presentations during annual events such as Learning Disabilities Awareness Month and the Mark it Read for Dyslexia campaign in October.

In turn, students with LD can help first-years by volunteering for support groups or mentoring programs. “It creates a sense of not being alone, and they can work out strategies together to have that social and academic space to support one another.”

Instructors can offer extra time to complete exams, avoid booking back-to-back midterms on the same day to avoid cognitive overload, and have Powerpoint presentations, open office hours and a few minutes before or after class available to answer questions for students with LD.

Most schools, like the U of A’s Academic Success Centre, also offer accessibility resources.

Ultimately, it’s important to help students with LD have a positive post-secondary experience, said Goegan, who plans to extend her research to the barriers they experienced during their transition to higher education, the skills they developed and how they define success for themselves.

She hopes to use her work to help develop orientation and mentorship programs that give students with LD a better chance of succeeding in their post-secondary careers.

“I hope that when they first come to campus feeling anxious, they come out of it feeling good because of supports put in place by everyone. We want them to feel like they grew, and it’s not just about the grade at the end of the day. We want them to think back fondly on the post-secondary experience they had.”

| By Bev Betkowski

This article was submitted by the University of Alberta’s online publication Folio, a Troy Media content provider partner.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.